Fleischers and Stoopid Buddies Used the Same Anti-Union Tactic Against Workers

Despite a span of almost 100 years between the two animation studios, the union busting playbook hasn’t changed much.

Two Studios, Two Letters

In the Fall of 2016, workers at the Los Angeles based stop motion studio Stoopid Buddies were on their second attempt to unionize the studio. A 5 page pro-union document, written anonymously (by a worker or workers), was being spread around the studio in the hopes of drumming up support and sharing information about the logistics and steps needed to take in order to unionize the studio. With stop motion studios being historically allergic to unionization for a variety of reasons, this was going to be no easy task. The last American stop motion studio to be unionized was in the 1940s with George Pal’s studio (1940-1947) under the Screen Cartoonists Guild.

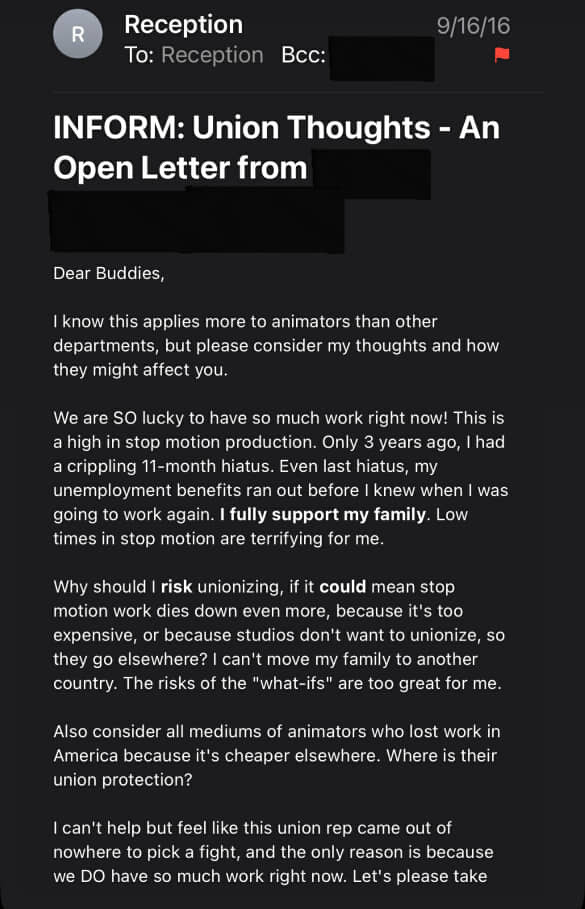

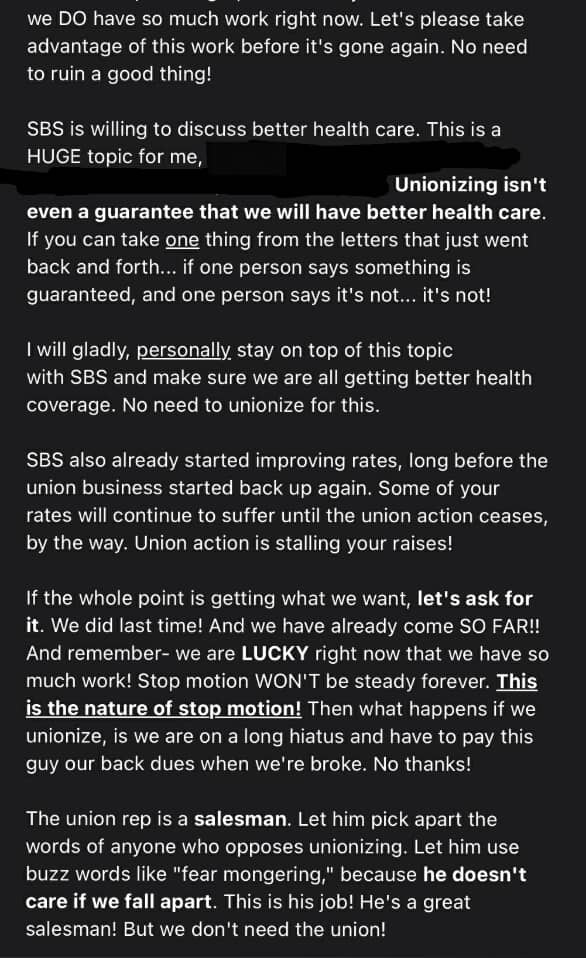

Despite being union members themselves (i.e. SAG, WGA), once the Stoopid Buddies owners became aware of the possibility of a growing pro-union sentiment among their own workforce, the retaliation was swift. On Sept 15, 2016 the studio spread a lengthy 8 page anti-union document around the studio, signed by all the studios’ founders: Seth Green, Matthew Senreich, Eric Towner, and John Harvatine IV. The next day, Sept 16, workers received an official email from the studio. This email was an anti-union letter written by a veteran animator at the studio, addressed to the studio workforce. Instead of the animator bcc’ing their coworkers on their own, the letter was shared with management first. Management then used its official’s reception desk email to send the anti-union letter to every current worker email they had on file. The animator (whose name has been omitted from the email screenshots below) touted the merits of the Stoopid Buddies owners while disparaging the union effort.

In 1937, the workers at Fleischer’s studio in New York City became the first animation studio to go on strike. The strike was a success and ended with the first union contract in the animation industry, which was with the Commercial Artists and Designers Union (CADU).

Two years prior, the studio was simmering with discussions of a union drive and the questionable deaths of two Fleischer employees. A young ink and painter, Lillian Oremland contracted tuberculosis in 1931. After taking a leave of absence, she returned to work but struggled to regain her health. She ended up having to take more time off, which at that point the studio refused to take her back. In 1935, Oremland died of her illness. Dan Glass, a young inbetweener befell to the same fate, succumbing to TB in the same year as Oremland. Fleischer workers were noticing a pattern they didn’t like. Many attributed these two deaths to the poor working conditions inside the studio. Poor air circulation, a lack of windows and AC combined with long work hours were seen as the culprits for Oremland and Glass’ early deaths, or at the very least, the studio worsen their conditions.

Today, we have no hard evidence that supports or denies the suspicions around these two deaths. But in the end, the point is that Fleischer workers saw a connection, which only added fuel to a unionizing fire that had already been burning for a while in the NYC animation scene. Oremland died after she had left the studio. Since Glass was the second death and also died while still being employed by the studio, his death garnered the most attention. It was a hot button issue in the studio. Max Fleischer knew it was getting harder to keep his workers at peace…and not unionized.

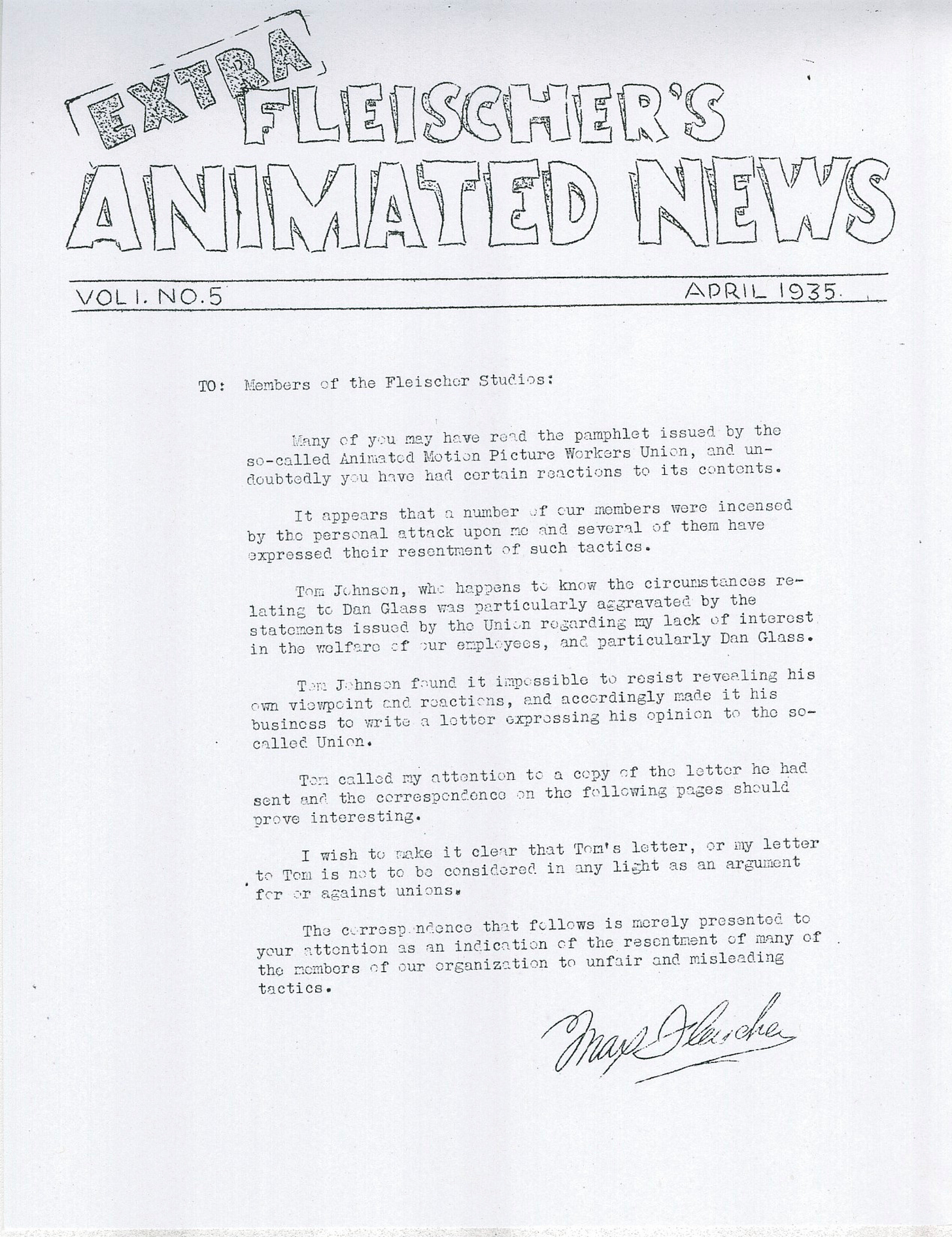

Three months after Glass’ death, Max Fleischer published a letter written by veteran animator at the studio, Thomas Johnson, in the official studio newsletter, Fleischer’s Animated News. In his letter, Johnson addresses the CADU (i.e. his pro-union coworkers), defending Max Fleischer’s treatment of Dan Glass and arguing against the unionizing effort growing at the studio.

Both letters can be read in full at the end of this article. Capitalization and bold lettering in the letter excerpts are original to the writer.

What was the goal of these personal letters?

At the time of these letters being published both animation studios had around the same amount of workers employed, about 150-170 ish. Both studios had the potential to make animation history if they were successful in their union drives. And lastly, both Stoopid Buddies and Fleischers used their official internal communication channels to disseminate an anti-union letter written by a veteran animator (of their own volition). With these factors in mind, I felt it made sense to have these letters put side by side.

These letters were an attempt to humanize the management’s anti-union stance. These letters are testimonials from a friend, a coworker, someone who isn’t the “greedy boss.” As an animation worker, you might be more compelled to listen to your coworker, someone who’s maybe in the same position as you financially or someone who’s knows what’s its like to be “in the trenches” with you on a daily basis.

Max Fleischer emphasizes this fact (maybe overly so) in his response to Johnson’s letter as printed in the newsletter, “Your letter is more significant in the fact it was written entirely on your own volition and in the further facts that you are in no way related to me, that you are not an officer of the corporation, that you are not in any managerial capacity and that you are one of our employees of five years standing.” Your coworker clearly isn’t speaking under the influence of any bigger power, right? So what they’re saying must be true…right? It conjures up the image of a magician waving their hand around their floating orb as to show “Look, no strings!“

Max Fleischer wrote in his preamble of Johnson’s letter, “I wish to make it clear that Tom’s letter, or my letter to Tom is not to be considered in any light as an argument for or against unions.” Despite these words, Johnson’s letter proved the contrary by having a plethora of well established anti-union talking points. Stoopid Buddies didn’t even try to include some shallow statement of impartiality before the animator’s personal letter. They were much more interested in a multi-day anti-union campaign in order to scare workers into complacency. In their letters, both animators present a sense of objectivity in their decision, that their conclusions have only come from deep thought and research.

Stoopid Buddies animator: I WAS IN FAVOR OF UNIONIZING LAST TIME. Then I looked at all sides. Because it DOES affect us all. I weighed the pros, the cons and the what-ifs.

Fleischer animator: I’ve observed your Communistic “Let’s take it” attitude. I don’t think this would be good for either the business or my career.

But what about the workers who also did a lot of research and deep thought that led to their decision to push for a union? Regardless of the claims in the letters, in the end the studios sent only an anti-union employee letter to their workers, not one letter for and one letter against. Since both Stoopid Buddies and Fleischer's management are/were vehemently anti-union, of course the material that is written in their favor will be sent to workers more openly, freely and through larger channels of communication. There is something to be said that the animators felt comfortable enough to sign their letters with their names, while the pro-union papers that were left around the Stoopid Buddies, and the pro-union cartoons and pamphlets spread at Fleischer'’s were always anonymous. There cannot be impartiality if one side is too scared of retaliation to speak freely. Even today, almost 10 years after the Stoopid Buddies unionization attempt, as former employees of the studio reach out to me and graciously share their screenshots and stories from 2016, the one recurring theme in our conversations is their adamant requests to stay anonymous.

In his letter, Johnson uses red baiting to defame the CADU, while the Stoopid Buddies animator called the union rep a “salesman” who “came out of nowhere.” Both letters paint unions as an invasive third party looking to use the studio turmoil to take money (without doing anything in return) from animation workers and strong arm the studio to the random whims of this outside organization.

Stoopid Buddy animator: …Some of your rates will continue to suffer until the union action ceases, by the way. Union action is stalling your raises!…Then what happens if we unionize, is we are on a long hiatus and have to pay this guy our back dues when we're broke. No thanks!…I cannot afford to pay the union to maybe change something here or there, and then keep paying them.

Fleischer animator: You could put me on strike at will. I need my salary 52 weeks in the year. Can you guarantee that? MAX FLEISCHER CAN!... I won’t split my salary with ANYONE!

Workers do need to pay dues to their union, since those dues allow the union to operate, however those dues can vary based on your income. Initiation fees are almost always waived for workers who unionize their workplace. Dues can vary from union to union and can be higher if they include healthcare or other benefits as part of the membership. If a union member is out of work, they can ask to have Honorable Withdrawal which means they don’t need to pay dues during that period of time. Unions have plenty of incentives to work with the employer as much as possible to find a compromise. If workers are unemployed they won’t be able to afford their dues and any payments the employers gives to the union that is based on number of active employees or/and their hours work (like healthcare, pension etc) will be greatly reduced. If management loses money and lays off workers or moves their business, the union loses members, money (as mentioned above) and its power is once again greatly weakened.

Another theme that should be noted is both letters emphasis on healthcare. Did Fleischer treat Glass’ illness with genuine concern? I do not have any information pertaining to the exact claims CADU made of Max Fleischer, nor do I have any direct quotes from Dan Glass himself. But while Johnson claims that Fleischer helped Glass after he became ill, it’s interesting to note that there is no discussion around implementing preventative measures at the studio for all workers. Things like more fans, opening windows, having more breaks, providing vouchers for jackets or lighter clothing (or just higher wages), are some of the various things that could have been put in to address the main issue of poor air quality and circulation at the studio. You could argue this might be even cheaper in the long run than Fleischer sending out employees like Glass to a ‘Jersey resort.‘

Johnson paints Glass as someone who is to blame for his own illness. Glass took night classes, he stayed at work even after Fleischer supposedly told him to leave early. It’s Glass’ fault that he got sick. And yet there is no awareness in Johnson’s letter about the American reality that ‘If you are not making enough money, if you cannot survive with what you have, you need to push yourself even if it kills you.‘ For example, if Glass knew that he wasn’t going to get paid his full shift if he left the studio early, what motivation would he have to go home? This is the 1930s, the Great Depression. To even have a job is seen as a privilege. It’s that job precarity and inability for workers to say no to more work, that Johnson does not appear to take into account when discussing Glass’ behavior.

For Stoopid Buddies in 2016, the main incentive for unionizing was getting better healthcare coverage under the union.

Stoopid Buddies animator: SBS is willing to discuss better health care. This is a HUGE topic for me…Unionizing isn't even a guarantee that we will have better health care. I will gladly, personally, stay on top of this topic with SBS and make sure we are all getting better health coverage. No need to unionize for this.

Stoopid Buddies only started offering healthcare after the passing of the ACA (Affordable Care Act) in 2014. The former worker I talked to for this article stated “We had a buddy round up where they were like "because of the ACA passing we are required to begin offering you healthcare.“ Many workers found their new healthcare options through the studio disappointing, and also tied to their employment which was only 4-6 months at a time, with no assurance of being rehired. And with the studio making it clear to workers that giving them healthcare was not an act of the kindness on their part, people hoped they could find something more robust with unionizing. The notion that one employee could convince multiple owners of strengthening the workforce’s healthcare seems a bit like grandstanding. You’re telling me one worker has a better chance of convincing a hostile multihead employer to invest more in their workers than a larger unified front? Mmmm..I don’t know about that bud.

Both letters end with a plea to replace the union drive with just good old fashion ‘let’s just be adults and talk it out with management’.

Stoopid Buddy animator: Let's please take advantage of this work before it's gone again. No need to ruin a good thing! …If the whole point is getting what we want, let’s ask for it…. If we need something, let’s get together and make it happen. We’ve been a team for a long time. Look how far we’ve come together.

Fleischer animator: But I do favor an organization! Its membership would come from those in the staff who realize that a Union means trouble in their business especially when composed of the Communistic “Let’s take it” element.

This argument unfortunately does not acknowledge the innate power imbalance between the worker and boss. Without any sort of collective power or proper grievance procedure, the workers do not have any leverage nor can they hold the employer accountable for their actions. For example, Stoopid Buddies could make workplace sexual harassment a main concern one day and then the next day drop all the promises and initiatives made on that subject. Improvements to the facility could be made while the unionizing process is taking place as a way for employers to show that “workers don’t need a union to have things change”, but very often once the unionizing talk is defeated employers have no motivation to continue and maintain those improvements. To say that utilizing the leverage workers have during a boom period to gain union protections as “ruining a good thing“ is extremely manipulative. Like any rugged old timey sunburned farmer chewing on a piece of hay will tell you, its important to prepare for famine during times of prosperity. *spits tobacco into spittoon*

Animator: The Jock of the Animation Studio Hierarchy

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that both letters were written by veteran animators. It’s common for people outside of the craft to assume that anyone working in animation is an animator. In reality, the animator is just one of the many MANY jobs in animation. Today, it’s honestly a bit of a dying breed in the mainstream US animation industry, as most animator jobs are outsourced when it comes to CG but mostly 2D projects. Historically, the animator was one of if not the highest paid job in the animation studio. It was THE job to have at the studio. Animators tended to be older than the rest of their cohort since they had already climbed through the studio ranks (starting out with cel washer, inker, inbetweener, layout etc). Since they had been at the studio longer they were much closer with the studio heads, often spending more leisure time with them (baseball games, dinner parties, etc) than with the rest of their coworkers. They would get special perks from the studio and if screen credits were given, animators for sure be included. They were treated like A-list actors in the animation social hierarchy. They were the ‘talent’ giving their performance on screen (via drawings/puppets). Because of this relationship, since the beginning of the US animation industry, animators have had a poor track record of supporting their coworkers (inbetweeners, ink and paint, opaquers, design and storypeople or others seen as “unskilled labor”) in their fight for better wages and fair treatment. Animators saw themselves as artists, while everyone else were “technicians” or “unskilled labor.“ I do want to note that I am not attributing this attitude directly to either letter writers, I’m just talking about the general vibe of animators historically.

In the case of Fleischer’s, only one animator respected the picket line of the strike, Eli Brucker. All other animators continued to go to work. Below are excerpts from three articles from the film trade newspaper, The Film Daily, that discuss the ongoing Fleischer Studios strike. You can see how the animators had a clear alliance with Max Fleischer throughout the strike, ultimately leading to animators being given the option to join the union or continue to have individual contracts with the studio. Bold emphasis in the quotations are mine.

This theme continued into the 21st century with the former Stoopid Buddy worker who shared the email screenshots with me mentioning that the SB animator writer in question “had more seniority at the time than me, so more to lose and a better relationship with the buds.” The SB animator began their email saying their letter “applies more to animators than other departments“. On the one hand it makes sense that an animator could only really address what is happening in their own cohort, but on the other it does show a lack of overlapping discussion among different departments at least on the part of the animator in question. Seems a bit of an oversight to deploy this workplace wide anti-union bomb without even checking in on how other departments are feeling about things. But the main reason to focus on animators was due to the department ending up as the cornerstone of the union drive this time around at the studio. Animators were spearheading many of the asks and demands and becoming more vocal with management. (There was no HR deptment at the studio at this time.) These demands, combined with the fact that Stoopid Buddies’ bread-and-butter show Robot Chicken is comedy that heavily relys on the labor of an animator’s performance to be successful, meant that animators were in a good position to have leverage with the studio if things got bad. So it appears the studio heads saw infighting and confusion and ideal solutions to this possible threat to their power.

From The Film Daily newspaper-

August 17, 1937

At an election held yesterday under the auspices of the National Labor Relations Board to determine whether or not the Commercial Artists & Designers' Union should represent artist employees of the Fleischer Studios as collective bargaining agent, the union received all of the 74 votes cast and claimed the right to represent the workers because it had received more than a majority of all votes. Nearly all of the votes were cast by members of the Commercial Artists & Designers' Union who have been on strike at the Fleischer Studios for three months. A total of 128 artists, of which 72 have been on strike, were eligible to vote, it was stated. Fifteen of the ballots cast for the union are being held aside until it is determined whether the voters were illegally discharged for union activities, as claimed by the union. The voting was held over the protest of Max Fleischer. According to the union, Fleischer posted a notice in his studios asking his employees not to vote in the election. Apparently many of them obeyed. Twenty-six out of 30 animators refused to take part in the election, according to Arthur Krim of Phillips & Nizer, counsel for Fleischer.

September 28, 1937

Fleischer Studios has agreed to recognize the Commercial Artists and Designers Union as exclusive bargaining agent for the production departments excepting animators. It will recognize the union as the bargaining agent for those animators who are union members and any other animators who may in the future become members. The union is yet to accept the proposed compromise.

October 11, 1937

Under the contract, Fleischer studios recognized the union and granted wage increases, a 40-hour week, vacations and sick leaves with pay and extra pay for overtime. The union made various guarantees of production. It was agreed that Fleischer studios had the right to deal and bargain with their non-union animators directly and not through the union. The new contract provides for arbitration of all future disputes. Strikes and lock-outs are prohibited. Under the agreement all employees return to work immediately.

The Aftermath

Stoopid Buddies: In 2016, there was a stop motion boom. There was work, and there was leverage for workers to use in order to get their unionization demands met. Unfortunately, the Stoopid Buddies owners pulled out all the stops to incite infighting, confusion and fear among its workers which lead to workers freezing in their tracks. The union drive ended before a single union card could be signed. Stoopid Buddies used fears of outsourcing to keep workers from asking for more, but in the end even after the unionizing attempt failed the studio went ahead and opened a new facility in Canada (which has now been closed for many years).

Many stop motion workers during that production season in 2016 were not hired back on for future projects at the studio. A former Stoopid Buddies worker, and source of the screenshots below explained that "after that season, many of us never got called back for following seasons despite being part of the studio’s regular hires.” Many of these workers suspected that they were not hired back on as an attempt to clean the studio of possible future unionization attempts. Since then, the leverage stop motion workers might have had is long gone, with the medium currently being in a slump at least in regards to the mainstream animation industry. At its peak, Stoopid Buddies had around 6 warehouses, plus shooting in Canada. “From around 2022 to 2024, the studio ended its lease on multiple buildings and sold off furniture and a bunch of their equipment. I think they’re down to 2 buildings now,” says the former SB worker.

Fleischer’s: Fleischer workers won their union drive with CADU in 1937 with the help of the studio’s distributor Paramount pressing Max Fleischer to acquiesce. Workers won many things including sick pay, vacation pay, paid overtime, increases in wages and a healthcare fund that employees and employers would pay into. Max Fleischer’s dissatisfaction with accepting the union was one of the reasons that led him to move his studio from NYC to Miami a year later. The massive cost of moving and operating an animation studio in a filmmaking desert combined with their first feature film being a massive flop, ultimately led to the studio shutting down. Paramount took back the studio from Fleischer, renamed it Famous Studios and relocated it back to New York in 1942.

Conclusion

Regardless of how old both these anti-union letters are, I still believe we, animation workers, can still learn a lot from them. They are good examples of the different fears that are instilled in the individual worker. A fear of scarcity, that there is a finite amount of jobs and money to be given out. A fear of punishment, that if we are not happy with the little crumbs we received from our employers, we risk having everything taken from us. A fear of precarity, that has allowed animation studios for almost a century to exploit their workers and take advantage of people’s love of the art form. This is just how the animation industry works. If you don’t like it, there’s the door.

I want to conclude this article with a reminder that these two animators should not be faulted for their decision to write these letters. They are not the problem and should not be the target of people’s frustrations with Stoopid Buddies, Fleischer’s, or the animation industry at large. The problem lies in the chronic systemic issues in the animation industry and the studio heads and execs who refuse to take the initiative in making animation work a sustainable profession. The intentional lack of labor education in the animation worker’s practice has led to workers being misled into thinking that their coworkers are the ones preventing them from having a better life. It has made people believe that volatility is intrinsic to the economics of animation and that it cannot be changed. But I want to believe in a better world for animation. If animation is known and celebrated for realizing the impossible, why can’t that ingenuity be applied to improving the lives of everyone working behind the scenes?

Fleischer Studios’ Working Conditions and Strike sources:

Deneroff, Harvey. “‘We Can’t Get Much Spinach’! The Organization and Implementation of the Fleischer Animation Strike.” Film History, vol. 1, no. 1, 1987, pp. 1–14. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3815036.

Dial, Donna. “Cartoons in Paradise: How the Fleischer Brothers Moved to Miami and Lost Their Studio.” The Florida Historical Quarterly, vol. 78, no. 3, 2000, pp. 309–30. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/30150575.

Hunt, Kristin. “The Great Animation Strike“ JSTOR Daily. January 2, 2020. https://daily.jstor.org/great-animation-strike/

Morton, Paul. “What Drove Popeye to the Picket Line: The Story of “Fleischer’s Animated News”“ Los Angeles Review of Books. Sept 19, 2023. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/what-drove-popeye-to-the-picket-line-the-story-of-fleischers-animated-news/

Stoopid Buddies Internal Email - Sept 16, 2016

Source: Former Stoopid Buddies Worker (Any identifying details have been redacted to preserve the anonymity of both the writer of the letter and the recipient of the email.)

Fleischer’s Animated News (In house Studio Newsletter) - April 1935

Source: Devon Baxter (https://www.patreon.com/devonbaxter)

Wow, super well researched and a fascinating historical comparison. The Disney strike looms so large in animation history that I admit I didn't know anything about the Fleischer's strike. Thanks for this!