8 Reasons Why Stopmotion Still Struggles to Unionize Today

Unraveling the various facets of stop motion's complicated labor struggles.

This quote is from a 2014 Atlas Obscura puff-piece about Screen Novelties. It still bothers me to this day. From talking to many stop motion workers over the years, I feel confident stating that Caballero’s statement is only a belief of studio heads, not workers. For a long time stop motion workers have been desperate to share with the public or at least with the animation cohort, their stories of triumph and failure, of meaty drama and labor actions, of insightful experiences and hurtful traumas. I don’t want stopmotion to be an opaque island in the entertainment field, I want to hope for something better.

Here’s some of the main topics I’ve heard discussed over the years about the various speed bumps on the road to stop motion unionization.

1. Unlike other countries, stop motion was not the foundation of American animation. Due to this reality, it missed out on being part of the animation industry’s successful unionization efforts in the first half of the 20th century. Instead of becoming a unionized field in animation, it became a non-union VFX (visual effects) tool for live action.

Despite stop motion or ‘stop frame animation’ being a foundational tool in early cinema, the American animation industry that we know of today arose from artists working in the world of newspaper comics and vaudeville (ex. lighting sketch artists). This is in stark contrast to many other countries in the late 19th/early 20th century who had their own animation productions originate from long histories of puppetry, like shadow puppetry or marionettes.

The first animated features in the UK (1945), France (1937), Belgium (1947), Czechoslovakia (1947), Germany (1926), and USSR (1935) were either fully stop motion or included stop motion segments. The first animated feature ever recorded, as well as the first with sound, was also stop motion (Argentina, 1917).

Meanwhile, there was an almost 20 year span between the first American 2D hand drawn animated feature in 1937 and its first stop-motion feature (that was not outsourced from the U.S) in 1954. Compared to other countries, the American animation industry seemed to be in no rush to recognize or invest in stop motion as a stand alone medium.

Despite stop motion production occurring in the same locations (Southern California and New York City) as 2D animation, they just didn’t seem to see each other as equals. Regardless, stop motion was quickly embraced by American live action for its ability to create fantastical characters with life-like movement that could be merged almost seamlessly with real actors and sets. Films like The Lost World (1925) (first feature film to make extensive use of stop motion animation) and King Kong (1933) helped cement the US as a pioneer in live action sci-fi, fantasy and creature features. Talk to an average American moviegoer today about “early American stop motion” and chances are high that the conversation will consist of figures like Willis O’Brian and Ray Harryhausen, maybe followed by mentions of Phil Tippett, the first Star Wars trilogy (1977-83), The Terminator (1984) and Robocop (1987). Rankin/Bass Christmas specials might be brought up as well, but despite being an American animation company, they outsourced all their stopmotion to Japan. Figures like George Pal, Art Clokey, Bruce Bickford and Will Vinton might come as afterthoughts, if they get mentioned at all.

There was only one stop motion studio that was able to gain a footing in the animation industry, allowing itself to become the first unionized stop motion studio in the process, George Pal Productions (1940-1947) located in Los Angeles. George Pal was an animator, director and producer originally from Hungary who eventually moved to the US in the late 1930s to flee the Nazis. With Paramount ordering a slew of stop motion /replacement animation shorts in Technicolor, known as “Puppetoons” from him and his team, the studio thrived. Many of Pal’s animation workers were also expats from Hungary who helped contribute the carpentry and fabrication skills necessary to make the sometimes thousands of puppets for each of their shorts. Quickly after opening, the studio was unionized under the Screen Cartoonists Guild with no issues and by 1942 workers were able to ensure a “closed shop” meaning everyone in the studio from animators, storyboard artists, wood carving/fabrication and more were unionized under SCG. Once Pal’s contract with Paramount expired, the studio closed with workers either following Pal back to Europe where he went on to produce and direct special effects heavy, sci-fi and fantasy live action films, or they got into American VFX. By the end of the 1940s, SCG had unionized almost the entirety of the American animation industry. Unfortunately it became a victim of Hollywood’s Red Scare and by the mid 1950s, the union had been broken apart and ceased operations. After George Pal, animation workers would have to wait until 2012 to see another unionized (albeit short lived) stop motion studio.

In addition to the American animation workers themselves not having pre existing skills of puppet/miniature fabrication, in the 1920s studio heads like John Randolph Bray were inspired by Taylorism and Henry Ford to devise the factory-like 2D animation studio pipeline that in many ways still is the norm today. By breaking down production into keyframes, in-betweens, ink and paint, studio heads could utilize cheap unskilled labor (women and young men) to produce shorts at a much faster rate for less money. I can see stop motion’s inability to be broken down to be more ‘cost saving and efficient’ as another reason why it did not appeal as a worthy investment to American studio heads at the beginning of the 20th century.

Modern American stop motion does not have a history of union contracts to build off of nor do they have robust labor solidarity with the 2D animation industry. Stop motion was offered steady work in live action special effects until computers slowly took over the field, leaving workers stuck in a limbo between being discarded by live action and an indifferent 2D/CG animation community that on paper would make sense to connect to, but the history just isn’t there.

2. Big time filmmakers with hectic one-off productions contribute to chronic instability and make it impossible for workers to build on any labor gains.

Aside from Laika, most mainstream high budget stop motion films in the US are usually one time projects dependent on outside financing by well established live action directors. With these directors already having a built in audience, a stop motion project can feel like a less of a risky investment for producers and distributors. Often this ‘live action auteur’ that the project revolves around will bring in a union crew at the very tippy top of the production food chain. SAG voice actors, WGA writers, composers or musicians under their own guilds, as well as live action directors under DGA. (Directors who come from animation are not allowed to join the DGA.) These unions can help those in power to have a positive experience throughout the production… while the non-union stop motion workers who create the product itself usually experience something much different.

Here are some examples of recent stop motion projects whose main selling point was their ‘live action auteur’ at the helm:

Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993) Tim Burton, Producer & Original idea by

Corpse Bride (2005) Tim Burton, Co-Director, Producer

Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009) Wes Anderson, Director, Writer, Producer

Frankenweenie (2012) Tim Burton, Director, Producer, Original idea by

Anomalisa (2015) Charlie Kaufman, Writer, Co-Director, Producer

Isle of Dogs (2018) Wes Anderson, Director, Writer, Producer

Guillermo del Toro's Pinnochio (2022) Guillermo del Toro, Writer, Co-Director, Producer

Wendall and Wild (2022) Jordan Peel, Writer, Producer and Voice Actor

I want to be clear that I am not trying to point the finger at any particular filmmaker nor is this about the merit of the films themselves. I am trying to talk about a pattern of financial production behaviors that benefit those in creative control (who more often than not are part of a live action union) who use stop motion as a stepping stone or a novelty for their filmography while turning a blind to the toxic work culture and unfair labor practices that often permeate within these productions.

Both Wes Anderson and Tim Burton have histories of being absent during the production of their stop motion films and being detached from their workforce, despite receiving the bulk of the praise of the final project. Live action filmmakers often enjoy having minute control over the fabricated world, but not the slower output of footage or the unique workflow. As you can see from the list above, live action auteurs often have a co-director or director with stop motion experience to shoulder most of the day to day production, giving them the leeway to go off and do something else while the stop motion workers are left to fend for themselves.

Sometimes these live action auteurs know what they are doing and sometimes they don’t. This pattern of live action auteurs taking more of a hands-off approach, only checking in every now and then can lead to normalizing established toxic workplaces even in the most A-List productions in the stopmotion world. Workers have to endure sketchy situations, often normalized by stop motion creative heads because no one “important” is looking. According to multiple stop motion workers I’ve talked to, the production of Anomalisa was fraught with alleged inappropriate behavior from its co-director (and stop motion veteran) Duke Johnson, and yet, Charlie Kaufman, with all his resources as a co-director and producer on the project, was nowhere to be found. In a beautiful world, live action auteurs could use their money and clout to promote and assure fair wages and a higher standard of labor in their stop motion productions.

Official film titles like,“Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio” and “Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas” further emphasize the idea that the live action star power is the main driving force of the project as opposed to a stop motion studio/auteur or the medium of stop motion itself.

This reliance on live action auteurs in marketing normalizes this concept that stop motion cannot stand on its own, echoing the early days of stop motion where American cinema decided it could only exist in aid of live action (through VFX). Distributors/producers believe that the medium is a money pit that is not worth investing in unless there is a live action auteur with a pre-existing fan base and deep pockets that can assist in carrying some of the financial risk.

Despite Tim Burton rarely being on the set of Nightmare, Disney (under the production label Touchstone Pictures) added Burton’s name in the title to capitalize on Burton’s success as a rising live action director, especially after the success of Batman (1989). During Nightmare’s production, Burton was busy directing Batman Returns (1992). That being said, how many tickets to Laika’s Coraline (2009) were bought under the impression that it was a ‘live action auteur film’ (Tim Burton), due to the film being sold as “from the director of the Nightmare Before Christmas”? This misattribution has cast a massive shadow over the career of Henry Selick (director of both Nightmare and Coraline).

Sometimes these live action filmmakers are presented as the saviors of animation, they are the ones who can bring ‘prestige’ to stop motion, as if the problem with stop motion is not the systemic labor issues crushing workers and gatekeeping creative control, but instead is just a general lack of creativity among animation workers. The idea that ‘animation workers are just mindless ants that need a leader outside of the medium to REALLY show them how to make a stop motion film’ is condescending and falls to acknowledge that live action studios/distributors themselves have been historically refused to finance or invest in innovative stop motion. How can stop motion be allowed to grow if all studios do is demand stop motion Christmas special, after stop motion Christmas special.

Often you hear live action auteurs in interviews talking about how they refrained from compositing out seam lines, used more old school harder to handle textures, like fur, and cotton balls, shot fewer frames per second and complained how stop motion workers today do things “too slick” with too much CG, pushing against the ‘modern look of stop motion animation’ (which is code for Laika). In stop motion, more so than any other animation medium, there is this fetishization of the ‘handcrafted’ nature of labor. You see ads of faceless workers and close ups of hands fabricating, sewing and building. These auteurs might praise the medium, they seem to have no interest in being part of the process itself nor to engage with the workers themselves.

Since Hollywood’s interest in financing stop motion ebbs and flows, there is no one sustaining studio that can tackle these large projects. Instead these films’ productions end up looking more like a traveling carnival, constructed around a singular filmmaker that only needs to stay up just long enough to do the job and no longer. These projects with tight deadlines and quick hiring windows puts animation workers at a disadvantage. It makes it difficult to standardize wages, build off gains from previous contracts/productions and improve working conditions over time in the stopmo industry. The volatile nature of the stop motion demand forces workers into a ‘take it or leave it’ situation. Demand more money or complain about workplace abuse and you might be kicked off a stop motion feature, without knowing when the next major stop motion project might be. It could be 6 months from now…or maybe 3 years from now, so it only makes sense to keep your head down and take what you are given, and be satisfied with it. If 2D and CG have struggled to maintain a stable inflow of work, then stop motion is worse.

While television is seen as more constant work for animation workers than film, it’s still an area where stop motion has struggled to maintain long term success. Stop motion shows usually don’t go past 2-3 seasons, and episodes are rarely a full 22 minutes.

3. Due to stop motion’s transient workforce, labor protections must take into consideration studio/state/country-hopping right from the start.

There is a very limited number of stop motion projects in the US at one given time. It’s a volatile industry. You often don’t know when or where your next job will be. Larger clients are fickle in how and when they choose to invest in stop motion. Maybe for 2-3 years there might be a stop motion craze, while the next 5 years the medium might feel almost dormant in the world of mainstream media. Due to this precarity, it’s extremely common for workers to bounce from different locations such as Los Angeles,CA, Portland,OR, San Francisco,CA, Canada, or the UK to follow whatever work they can find, sometimes moving their whole family in the process. For a stop motion worker to spend their whole career under one employer is almost an impossibility.Working on one project for over a year is beyond a rarity. As a result of this gig economy like structure, going the traditional route of unionizing a studio can be very difficult as that requires some level of stability on the part of the business and its workers. When you’re dealing with short contracts that can range from days, weeks, to months at most, it's hard to have the time to get together with folks and slowly build solidarity and trust. Unionizing takes time and planning. It can be an uphill battle at first, as workers need to have one on one conversations with each other to strategize, collect data, educate and garner support among each other, especially when there is no previous union culture to build off of.

This is by no means only a stop motion problem, it’s a worldwide issue of trying to organize as workers jump from gig to gig. If stop motion workers were to unionize, that effort would have to have to be a national (and then international) effort. Union benefits would have to cover the stop motion worker and follow them around, as opposed to just being connected to their employment at one studio.

Live action unions (like SAG, Actor’s Equity, IATSE etc) have branches across the country as well as partnerships with other unions internationally. IATSE (International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees), the Animation Guild’s parent union covers the US as well as Canada. Despite IATSE’s wide stretch, the Animation Guild only ratified its first non-California union contract in 2023 while IATSE’s Canadian Animation Guild was founded in 2020 and currently only covers British Columbia.

Working together with different international unions in animation is not new nor is it impossible. Animator, animation historian and TAG President Emeritus writes in his 2006 book, Drawing the Line: The Untold Story of the Animation Unions from Bosko to Bart Simpson:

“To keep.. [the production of Who Framed Roger Rabbit? in the mid 1980s]..midway between Disney and Spielberg’s Amblimation, it was agreed that the animation would be done in London with a crew led by Richard Williams. There was a London animation trade union, a division of BECTU (Broadcasting Entertainment Cinematograph and Theatre Union), the British equivalent of IATSE. An accommodation was made for American artists working under Local 839 contracts in London.”

So just because a gig is short or workers move around does not mean that they can’t be unionized. If traveling writers, actors and crews on stage or screen can be unionized then stop motion workers can do the same.

4. With stop motion studios constantly in a precarious state, studio heads will often claim that unionization (i.e. increased wages) will bankrupt a medium that is already struggling to compete/survive in the American animation industry.

Most stop motion studios are small and so have often used the rhetoric of “We are always financially struggling and therefore cannot unionize because the resulting increase in costs would either lead to the studio closing or leaving the country”. Larger studios, brands or other companies that seek out stop motion, force stopmo studios to engage in bottom of the barrel bidding, creating a race to the bottom where stopmo studios keep lowering their budgets and tightening their deadlines while making larger than life claims on the quality of their product, leading to stressful and dangerous working conditions for its workers.

Claims of outsourcing and studios closing in stop motion are used as an underlying threat to prevent workers from even thinking about unionizing. But the truth is that those problems are already occurring in full bloom regardless of any ongoing unionizing effort. These studios constantly make poor financial decisions completely on their own. They mishandle contracts, make promises to clients they can’t keep and bankrupt themselves. Outsourcing cannot be a credible threat because it's already been happening for decades. There is no current stop motion utopia to be lost at the moment by unionizing.

Ideally, if unionizing were to happen one studio at a time, Laika in Portland, Oregon, would be the ideal place to start, as the studio is the largest and arguably the most financially stable in the field due to being owned and bankrolled by Nike founder, Phil Knight. Knight’s son, Travis is the President & CEO of Laika. Theoretically, Laika has the resources to pay their workers more and weather any kind of financial storm that might occur during the initial unionization process. Despite Laika’s history of hit or miss films, they continue to be able to operate due to Knight’s wealth.

But obviously, just because Laika HAS money and CAN afford to pay workers more doesn’t mean they will. Phil Knight and Nike have a very long history of exploiting workers, sweatshops and violating labor laws. And it goes even deeper than just business ventures, one could argue that Knight sort of holds Oregonian politics, higher education and sports hostage due to being the state’s wealthiest person and the largest individual donor, with his political donations always exclusively being for Republican candidates and causes.

Of course, having the largest American stop motion studio unionized would be a great first start in standardizing the field. But at the moment Laika appears to be a non-union stronghold, with no hint of Travis Knight veering from his father’s beliefs. There have been multiple attempts to unionize the studio over the years, but the retaliation has always been immediate and swift.

Ultimately, to say that stop motion can only unionize if the studio has money is an excuse that appears often but doesn’t have much to stand on. Unions don’t want studios that their workers operate in to close or move, because then the union would lose members. Unions have plenty of incentive to work with employers to find strategy within their means. Companies have the freedom to financially disclose their budgets to their unions in order to work together to look over costs and negotiate wages that increase over a period of years. Employees and employers can work together to meet halfway so that the business can operate within their means but also have workers be respected and be paid their worth.

5. With stop motion workers dealing with elements of live action, puppetry, theater and animation in their day to day work, jurisdictional confusion arises as workers struggle to find the best union/s for them.

The question of jurisdiction around stop motion labor is a topic that usually ends up giving workers more headaches than answers. On the one hand, it would make sense to put EVERYONE in stop motion animation, into The Animation Guild since its animation, right?

But then on the OTHER hand, you could argue that despite stop motion being animation, its production needs have far more in common with a live action shoot (ie physical sets, lighting, costumes, props, fabrication) than a 2D animation pipeline, therefore stop motion should be part of live action labor unions.

While both positions make sense at a basic level, each one has caveats that have led to folks being stumped as to where to go for support in labor organizing.

Position 1: “Stop motion belongs in the Animation Guild.”

The Animation Guild has never had a stop motion studio under its jurisdiction, with the one exception being the extremely short lived Cinderbiter Productions, headed by Henry Selick, funded by Disney and located in San Francisco. In September 2011, TAG announced that they were “repping animators under an IA-Disney contract” at Cinderbiter, which I assume then meant that the rest of the production was filed under various locals under IATSE, in a type of hybrid union contract.

We don’t know if this arrangement would have worked in the long term since Disney abruptly closed the studio the following year while Cinderbiter was in mid production for its first film “Shadow King”, laying off around 150 stop motion workers in the process. From talking to stop motion workers, it appeared it was Disney who required the stop motion studio to be union. This brings up the point that another possible way stopmo could unionize is by just having the stop motion studio’s distributor or financier (or the live action auteur as mentioned earlier) put their foot down and say “unionize or we won’t work with you.” Maybe that might seem far-fetched to some, but it's worth putting on the table as another way to leverage power against stopmo studios heads with actively anti-union stances.

TAG has a long history of being understaffed and known widely in the animation world as weak, ineffective. The trust between its members and leadership is quite poor. If TAG cannot properly provide for their current 2D/CG members, it's understandable that they would lack the bandwidth and resources to create a new template contract to accommodate stop motion animation needs which involve more provisions in terms of dealing with air ventilation, injury prevention/redress, chemicals, and other hazardous materials that someone working at a Cintiq might not have to deal with on a daily basis. That being said, I do want to emphasize that TAG does not need to continue this pattern of inefficiency. There are many TAG members working tirelessly to reform the union from the inside out and I don’t want my criticism of TAG leadership to be directed upon the thousands of TAG members who desperately want a union that protects their craft, ensures them livable wages and is more proactive rather than reactive to the changing landscape in the entertainment field. In the past few years over six thousand workers across the tech and video game industry in the United States and Canada have now unionized with Campaign to Organize Digital Employees–Communications Workers of America (CODE-CWA), even though again you could technically label video games under ‘animation’. VFX, another field that could be labeled as ‘animation‘ has done a unionizing drive over the past few years with IATSE, not TAG. Animation directors have wanted to be part of DGA for a long time and animation writers want to be covered by the WGA, as both unions are stronger with better benefits than TAG. With these different elements in mind, you can see how stop motion workers aren’t running over themselves to be part of the Animation Guild.

Position 2: “Stop motion belongs in a live action union (like IATSE).”

Stop motion can be defined as a slow moving live action set despite the end product being animation, so it might make sense for workers to go with IATSE, the largest labor union in the entertainment business (and the parent union of the Animation Guild). A lot of what stop motion workers do already fall under IATSE jurisdiction, with some scattered workers already in IATSE locals depending how often they work on live action projects.

The main problem with IATSE is how large and lethargic it is. It lacks the aggression needed to fight a film world that has actively pushed its crew and production workers to the brink of desperation and poverty. Over the past two years there has been a slew of fatal accidents that have befallen IATSE workers due to either dangerous work conditions or driving sleep deprived (due to long shifts). In its 131-year history, IATSE has never staged a nationwide strike which in my opinion is an absolute embarrassment for a union that’s over a century old. In 2021, 98% of IATSE members voted to approve a strike authorization vote as the union negotiated a new contract with the AMPTP. Despite the overwhelming support for a national strike, union leaders never called a strike and reached a tentative agreement with the producers a week or so after that vote had been called. Then when the TA was voted on by IATSE members, despite most workers opposing the new contract, it was still ratified.

Like any basic level union, IATSE and/or TAG supposedly could ensure stop motion workers something that looks like wage minimums and healthcare, but having to choose between the two is kind of like being hungry and having to choose between a wet sandwich and moldy fruit. :^|

Position 3: “Stop motion belongs …somewhere else?”

Those who work in the world of puppetry, like Jim Henson Studio, also have very similar union issues that stop motion has: confusion over jurisdiction, workers exposed to hazardous chemicals and materials on a daily basis, and a lack of interest/concern from unions in jumping in to meet the workers halfway. In puppetry, only puppeteers can be represented by SAG while stop motion animators were the only ones represented by the Animation Guild when Cinderbiter had that hybrid union contract. These arrangements still leave behind a lot of workers that are integral to these productions. What if there was a separate union for all puppet folk that would cover both stage and screen? Anyways the basic fact remains that for over a century, live action sets have been able to run smoothly with hybrid labor contracts and multiple unions working on one production, so stop motion should be able to do the same without issue.

6. Stop motion’s systemic issues around misogyny, sexual harassment, and discrimination (with no recourse for victims), makes it a difficult place to generate across the board solidarity.

It’s hard to describe the sheer amount of stories I’ve heard from stop motion folks about the bullying, microaggressions, racism, homo/transphobia, sexual harassment/assault and derogatory remarks that women/POC/queer folks have had to endure on a daily basis at various stop motion studios.

Questioning a minority's technical capabilities, making inappropriate comments, superiors sending unsolicited texts and images in the middle of the night to subordinates… the horrible things that stopmo workers (who aren’t cis straight white males) have had to endure is vast and seemingly unending once you start poking around. I’ve heard from some veteran stop motion female workers that they felt they needed to take on a persona of being “be one of the guys’ in order to be accepted into the world of ‘stop motion bros’ and be assured future employment. These women would participate or goad the crass humor at work or do their best to keep up with the rampant drinking culture in the studios despite their inner reservations as they believed it was the only way they could be assured constant work in the field with limited options and gatekeeping tendencies. Who knows how much talent and innovation American stop motion has lost over the years by workplaces inhospitable to those who couldn’t fit into the “stop motion bro’ culture?

Despite the first surviving animated film (that was stop motion as well) being animated/written/directed by a woman, the world of animation has been male dominated for a long time. And with live action crews (lighting, camera, set building, etc) also mainly being men, stop motion combines the two worlds and ends up reeking of toxic masculinity. Studios like Stoopid Buddies, Laika, ShadowMachine and more are notorious among workers for their sexism but unfortunately there are few or no options for recourse. Few stop motion studios have HR departments and even if they do, they naturally concern themselves with how to protect the studio instead of solving the problem in a meaningful way and protecting the worker being victimized.

Men will gatekeep job opportunities and expertise, choosing to mentor workers that look and act similar to themselves. Problematic men will stay around studios because they have specialized knowledge or because they are the “only one who knows how to operate this machine or do this special technique.” It’s hard to call out a problematic coworker when you know that they might be the director on the next project or maybe best friends with those in higher positions. What motivation do you have to seek recourse when you know speaking up could lead to you getting kicked out of the stop motion field?

But also on the other hand, why would you want to work together with these people on unionizing? Unionizing means having in-depth conversations with many coworkers, having meetings outside of working hours, setting up surveys, spending hours and hours writing contract proposals and reaching out to as many stop motion workers as one can. You need to talk a lot to those around your studio, and eventually do need to have a majority of the workers in support of the union. But if for example you’re a minority in the studio and you don’t feel safe, don’t trust that your cohort will respect your opinions, and just dread the prospect of having to spend your after hours talking to problematic coworkers, organizing might feel even more out of reach.

7. Stop motion’s small community combined with an overlapping studio workforce leads to extreme fear of blacklisting, rumors, and retaliation.

You’d think that a small workforce would be easy to unionize logistically but that’s not always the case. Since studios frequently share talent, with the same set of workers migrating from one production to another, any form of back-talk or dissent travels quickly across the field. Stop motion workers I’ve talked to have repeatedly expressed their frustration around needing to endure chronic mistreatment on multiple levels due to the limited production options that are available at one given time. Your behavior and your connections on one production can directly impact your ability to be hired onto maybe the only other stop motion production occurring at a different studio later in the year.

A frequent obstacle I face when trying to talk to or interview stop motion workers on the record is their fear that even if their name is redacted, details such as studio, job title and/or name of production are more than enough for other workers (and studio heads) to make a quick calculation and figure out who the worker is. That worker can then face studio retaliation, job loss and blacklisting as a result. The stop motion world is that small.

Over the years, the main way I’ve seen stop motion workers be able to create solidarity and support amongst their ranks is Stopmo Industry Stories, an Instagram account where stopmo artists can anonymously vent, ask questions and garner support from one another around work abuses that the rest of the animation industry (and the film world in general) seem indifferent to.

8. “Stop motion is a dying art, so what’s the point of trying to unionize it?” This thought leads to the question of stop motion education and training. How can we bring a more diverse workforce into stop motion that knows their rights as workers?

As mentioned before, stop motion gigs are very limited. Since competition to fill positions is high, there isn’t much of an incentive to bring in tons of new talent into the field.

Unlike 2D or CG, there are no college level stop motion specific animation programs. Usually if an animation student wants to make a stop motion short, it’ll be up to them to find stop motion electives, if the school has any, and dig around their department to find the resources they need to make their project a reality. These electives tend to focus on the technical and artistic aspects of stop motion (how to light a scene, build a puppet, etc) and might not go over labor focused topics such as posture awareness, stretching, how to build sets that reduce the need for folks to contort themselves when working, putting mats on surfaces where you stand a lot, taking breaks and how to read or haggle a contract.

Some stop motion studios do offer paid classes/workshops, like Stoopid Buddies, but naturally you aren’t going to find anything close to workers’ rights education at these courses. I wouldn’t be surprised if these classes even mislead aspiring stop motion artists, blinding them with the novelty of working at an ultra cool stop motion studio… only for the studio to then later use that passion and excitement against the artist. Once that young artist burns out, it's ok because they’ll always be another passionate but naive artist right behind them ready to take on the horrid conditions…only to eventually burn out, and so the cycle continues.

Most stop motion workers’ education comes from being on the job, but as mentioned before, sometimes it can be difficult to rely on older stop motion workers for mentoring when they are kind of… racists, homophobic, sexist white guys. They might not be willing to teach everyone their tricks and tips.

I find it ironic that while the industry remains so small, insular and sort of secretive, stop motion itself is the most accessible form of animation. It’s usually the first type of animation that people interact with when starting their exploration in the medium, both children and adults alike. Cut out animation, claymation creatures or Legos in front of a camera. A penny being moved around under a down shooter to learn about weight and easing. You don’t need any drawing experience to do stop motion, just a sense of movement. Anything is fair game in stop motion; sand, paper, dolls, trash, humans, food, clothes, dead bugs, dirt and more! It’s a shame that the vast expanse of stop motion and all its possibilities end up getting lost somewhere on its journey into the professional field.

Maybe we need different ways to enter the stop motion field? Coming out of left field might be a better way to establish stop motion studios with new standards of workplace culture. Is playing the long game to rise through the ranks at existing but problematic studios really be the only way at improving things? How can education/training help stop motion workers (both professionals and students) be more confident in their rights as a worker? Or help them branch out to create stop motion studios or collectives that uplift minority voices in a safe, equitable and respectful environment?

So what’s the conclusion?

Well in a weird way, there is no conclusion. This is an ongoing area of research that needs more articles, interviews and data in order for both stop motion workers and fans to better understand the different facets and overall scope of stop motion labor issues.

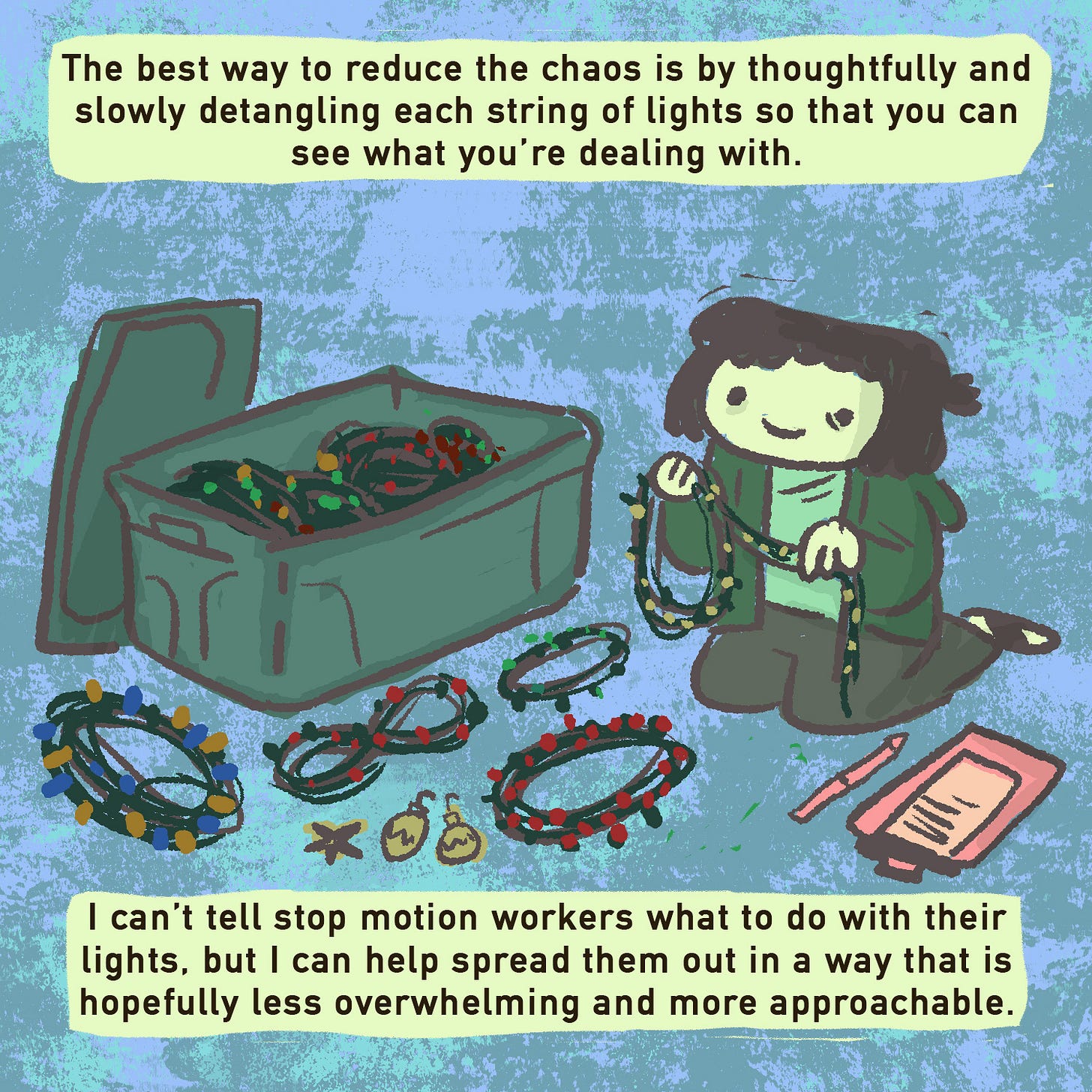

There have been multiple attempts to unionize at various stop motion studios like Stoopid Buddies and Laika, but since there is no larger conversation going on we can’t see patterns and build on communal experience. Most of the stop motion workers I’ve talked to are completely demoralized and don’t even want to expend energy on discussing this topic. I understand the frustration. It’s hard to hope for something better when everyone around you might immediately shut down the conversation with statements like “Unionizing doesn’t work in stop motion.”, “Nobody cares about stop motion.”, “This is just how stop motion has always been, if you don’t like it leave”. Unionizing might seem like a big mountain to climb at the moment, but everything starts with simple steps. Keep talking about your stop motion work issues with coworkers, friends, family and loved ones. Your pet. Your stuffed animal. Talk to literally anyone who will listen. Talk to coworkers you trust about wages, benefits and red flag coworkers, and just for funsies, brainstorm with your coworkers what your ideal working conditions would be in stop motion. What benefits would you like? Wages? Schedule?

Anyways, I’ll just end this with some tiny steps stop motion workers (or any worker) can do to give themselves just a little bit of control back in the workplace.

Remember to document, document, document! Screenshot questionable texts, save weird emails, take photos of safety issues (in a low key way) at work. Write in your phone, diary or somewhere else quotes or comments someone made at work that wasn’t cool, maybe it was gross, condescending etc. Don’t forget to include the date and any other helpful information. I know it can be extremely difficult to try to think about archiving during a time that is deeply hurtful or even traumatic. Collecting evidence can help protect ourselves from gaslighting and other nefarious means others might use to deny our own voice, experiences and feelings. These materials can also be used in the future to help you identify toxic patterns to watch out for over multiple jobs, better compare experiences with coworkers, aid in communicating workplace issues to coworkers, friends and loved ones, support your comments in a media interview or if worse comes to worse, aid you in filing a claim with the state. If someone in management tells you something sketchy orally, whether it be in person or on the phone, email them later asking for confirmation, something like “Hi just wanted to confirm that you want me to do XYZ /you are going to pay me XYZ for this project.” Once they reply, you now have written documentation of their request, which makes it less likely that they will alter, rescind or deny your conversation should something odd occur down the line.

In the end, it's all about small steps.

Detangling one christmas light at a time.

This was very insightful and I’ve learned a lot! Thank you.